On “Cultural Marxism”

The following is an excerpt of the author’s manuscript-in-progress, due for publication at the end of 2022, on the phenomenon and inherent problems of “Woke” Ideology.

This excerpt can be downloaded as a PDF here.

Very often, leftists are accused of being “cultural Marxists,” a pejorative term used often by far-right and pro-capitalist theorists who detect in social justice movements an attempt to infiltrate cultural, educational, and legal institutions. The goal, as their accusers would have it, is to undermine traditional values and stable societies in order to prepare the way for large-scale revolution.

Cultural Marxism is a conspiracy theory. However, as Erica Lagalisse points out in her work The Occult Features of Anarchism, conspiracy theories function so well specifically because they contain an obscured underlying truth which the conspiracists mis-identify. For instance, consider the many antisemitic conspiracy theories proposing a global cabal of Jews who pull the strings of world leaders. These theories are quite dangerous and obviously false, but they are able to hold power because of a kernel of truth within them. Extremely rich individuals, investment banks, multinational corporations, and international governance and non-governmental organisations (the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, the World Economic Forum, the Charles Koch Foundation, the Open Societies Foundation) all exert incredible and anti-democratic control and influence over individual nations and their societies. That is, there is absolutely a global cabal, but it’s not a Jewish cabal.

The conspiracy theories regarding Cultural Marxism likewise contain a kernel of truth. In fact, to be blunt, many leftists indeed do believe that institutions and culture itself must be changed in order to make society more free. The particular conflicts in the United States regarding declarative gender theory and Critical Race Theory (CRT) in early public education, while often rife with hyperbole and extreme reactions, nevertheless derive from actual changes in pedagogy designed to change cultural frameworks.

Regardless of which side one takes on such issues, a few things need to be noted. First of all, social justice movements for cultural change are hardly unified or even co-ordinated, and also often conflict with each other. In other words, there is no global “Woke” cabal, but rather a dispersed and very chaotic set of populist movements attempting to change culture according to their particular ideas of what constitutes an ideal society. Secondly, and more importantly, none of these movements have any real relationship to Marxism in any traditional sense of the idea, since none actually argue for class revolt.

In fact, what conspiracy theorists call “Cultural Marxism” is not Marxist at all, and even often inimical to Marxist class analysis. To understand how this is the case, we need to first look at the historical processes which created the movements falsely identified as Cultural Marxism.

Utopian Socialism Versus Communism

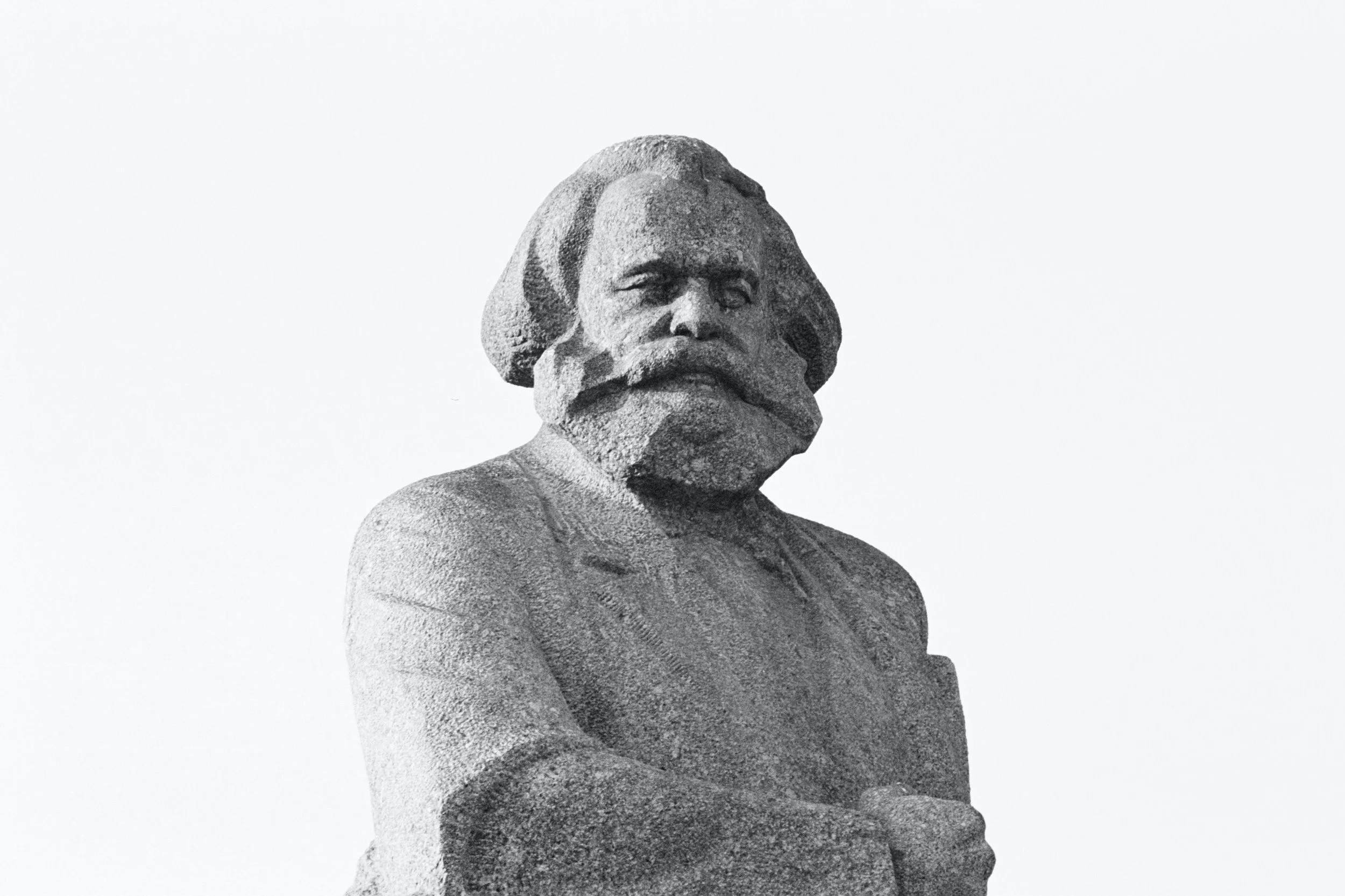

Conspiracists often point to an institution and intellectual tradition called The Frankfurt School (or The Institute for Social Research) as the progenitors of the theory of Cultural Marxism. Before looking there, however, we need to go back a bit further in history to the time of Karl Marx himself and the movement he opposed, Utopian Socialism.

Socialism did not start with Marx nor with The Communist Manifesto, but rather arose from French, English, and American thought during the so-called Enlightenment. Socialism as first iterated was an intellectual movement and framework arguing for the redesign of society from above in order to make it more equal. That is, it was a response to lower class, populist anger about the inequalities and misery caused by industrial capitalism, and it was offered as a way to meet those demands through changing society culturally, legally, and institutionally.

Socialism as it was first iterated was utopian in nature, meaning that early socialists believed it was possible to have perfect societies. Drunk on the heady beliefs of the Enlightenment, the early socialists theorized ways of designing society in such a way that everyone would be his or her ideal self, equal, fulfilled, and productive. The ways they imagined, of course, were often mere re-toolings of the same utopian imaginings of engineers, factory owners, accountants, race scientists, and others of the new class of urban intellectuals arising during the birth of industrialism.

In other words, early socialism was a management theory, just as the bourgeoisie can be said to be a management class. Humans could all live better together if they right conditions were created, just as workers could be more productive if the right machines were designed and the ideal discipline adopted.

For both the bourgeoisie and the utopian socialists, key to ushering in the ideal utopian society was education. Teaching peasants and the urban poor how to act civil to each other, “enlightening” them through pamphlets, primers, and schools to become active and informed participants in political and social life, and also instructing the ruling classes in more humane and effective modes of governance and punishment were all fundamental to their utopian visions.

It was against both capitalism and utopian socialism which Marx and Engles reacted. For them, there could be no material change in the lives of the poor without physically seizing the means of production from the rich. Karl Marx saw the utopian socialists as hopefully out-of-touch with the lower classes they claimed to want to help; even more so, Marx saw them as ultimately enemies of those lower classes.

W e can see historically that Marx’s arguments resonated more strongly with the working class, since communism as an alternative to utopian socialism soon became a powerful revolutionary ideology. Utopian socialism, on the other hand, argued against revolution and often came to be seen as inherently counter-revolutionary.

This tension helps us understand already a core conflict between Marxism and the populist social justice (“Woke”) movements occurring today, as utopian socialism later became what we call Progressive (and “Left-liberal”) politics in the United States and Social Democratic politics in Europe. Neither of these current moments argue for revolution nor even changing the core relationship of capital to the working classes, instead focusing on changing social conditions for minorities and lessening the pain of capitalist exploitation through social welfare programs.

There’s much more to the story, however, as I’ve just skipped an entire century, the 20th century. That period saw both massive communist revolutions and their defeat, as well as the rise of a competing ideology which ripped apart Europe and created the industrial death factories called concentration camps.

In fact, the story of the Frankfurt School and of so-called Cultural Marxism cannot be told without looking at the rise of Fascism as a political ideology and why it succeeded in capturing the minds of so many where both communism and utopian socialism had failed.

Gramsci and the Cultural Vanguard

If there is a father of “Cultural Marxism,” he is Antonio Gramsci, a communist imprisoned in Italy for his opposition to Mussolini and fascism. Gramsci devoted much of his writings while in prison (he died while serving out his sentence in 1937) to understanding why communism had failed in both Germany and Italy and why fascism managed to take such a strong hold.

Gramsci concluded that communists in those places had never managed to create a cultural revolution to prepare the ground for actual revolution. He asserted that there were two types of revolutionary strategy both required to liberate the masses from the capitalists, the War of Position and the War of Maneuver.

The latter strategy, the War of Maneuver, is what we generally think of as revolution: the physical acts, strikes, and seizure of institutional power which compose the actual transition from an old order into a new one. However, these maneuvers cannot be accomplished without first instilling into the masses a revolutionary consciousness, which requires a War of Position.

Gramsci argued that the War of Position requires changing the cultural forms and beliefs of the working classes in opposition to the cultural hegemony of the capitalists. In order to actually desire to revolt, the masses must first understand how they are being exploited and how the cultural institutions they accept as natural or good are actually created to harm them. This means changing the beliefs of the masses, including teaching them to stop relying only on their common-sense observations of the world, which can only perceive the situation within the capitalist social order itself.

For Gramsci, this shift is only possible if the working classes develop, support, and listen to their own intellectuals in opposition to the intellectuals of the bourgeoisie. In his conception, every order produces intellectuals, the dominant order produces its own the artists, writers, journalists, scientists, and other intellectuals who, because of their privileged position within the capitalist order, will inevitably only ever argue for its continuation. Further, because the masses need to rely upon intellectuals for an understanding of the world which their individual common sense cannot provide, a position in which there are only intellectuals upholding the dominant order ensures there can be no other future.

Gramsci asserted that the capitalists can only be overthrown if a new kind of working-class intellectual arises, one who is part of the working classes yet who has simultaneously risen above the limiting common sense of the masses. These intellectuals must fully give themselves over to the task, becoming “permanent persuaders” in Gramsci’s words, and must ultimately provide a popular cultural framework which can compete with the cultural hegemony of the capitalist order.

To put this all more simply, Gramsci extended the anarchist (and later Leninist) idea of the vanguard into culture. A cultural vanguard—in other words, an elite—was a necessity for any successful revolution, Artists, journalists, scientists, and others were needed to create cultural forms that could compete with the capitalist forms, and once they succeeded in their War of Position, the War of Maneuver (the actual physical revolution) could proceed.

The Frankfurt School

I asserted earlier that Gramsci could be named the father of Cultural Marxism, but of course the term Cultural Marxism is more often associated with the subsequent theorists of the Frankfurt School.

The Frankfurt School was founded initially in Germany but later relocated temporarily to the United States during the Nazi regime. Many of the academics associated with the Frankfurt School were either Marxist or used Marx’s analyses of the relationship between social and material conditions in their own theories. Additionally, though their ideas were not monolithic, a general point of agreement was the Gramscian ideas of cultural hegemony and that social change was a prerequisite for a change in the material conditions of humans.

Theodore Adorno, in particular, is often cited as the primary architect of the conspiracy of cultural marxism. However, one of the most common criticisms levied against him by Marxists (his contemporaries and those living now) is that his work relied both on a misinterpretation of Marx and a complete rejection of Marx’s optimism regarding the potential of the working classes. At least in this second aspect, his critics appear correct, as Adorno is deeply pessimistic regarding the masses.

Experiences in Adorno’s own life no doubt contributed to his pessimism, including the rise of National Socialism in Germany (which caused the Frankfurt School to exile itself in the United States), and later interactions with radical students which seem to shockingly to prefigure the eructations of Woke activism in our current day.

After the May uprisings in 1968, the student movement in West Germany had begun to extend their criticism of capitalism to academics who either did not go far enough in their critiques or who, to the students, represented a reactionary traditionalism inimical to revolution. Many of their ideas were inspired by Adorno, Habermas, Marcuse, and others of the Frankfurt School, which makes what then happened to Adorno seem not only ironic but almost hilarious.

Early in 1969, a group of student protestors led by Hans-Jürgen Krahl occupied a room in the Institute for Social Research and threatened Adorno, leading him to call the police to have them removed. This came after several months of criticism regarding what he saw as their brutish and undirected tactics—though he supported their goals, he also came to fear the rage they directed at academics and their lack of analysis regarding fascism.

A few months later, in April of 1969, on the opening day of a new lecture series on “Dialectical Thinking” that Adorno offered, a student action occurred: attendees began to shout and otherwise harass him, while another wrote on the chalkboard “If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease.” This action, called the Busenaktion (breast action) ended with three female students surrounding the old man, baring their breasts at him, and covering him with flower petals.

Adorno would later write to his colleague, friend, and the former director of the Institute for Social Research that the student movement he and Marcuse had helped inspire was in danger of converting to a kind of “left fascism.”

“I would have to deny everything that I think and know about the objective tendency if I wanted to believe that the student protest movement in Germany had even the tiniest prospect of effecting a social intervention. Because, however, it cannot do that its effect is questionable in two respects. Firstly, inasmuch as it inflames an undiminished fascist potential in Germany, without even caring about it. Secondly, insofar as it breeds in itself tendencies which— and here too we must differ—directly converge with fascism. I name as symptomatic of this the technique of calling for a discussion, only to then make one impossible; the barbaric inhumanity of a mode of behaviour that is regressive and even confuses regression with revolution; the blind primacy of action; the formalism which is indifferent to the content and shape of that against which one revolts, namely our theory. Here in Frankfurt, and certainly in Berlin as well, the word ‘professor’ is used condescendingly to dismiss people, or as they so nicely put it ‘to put them down’, just as the Nazis used the word Jew in their day. I no longer regard the total complex of what has confronted me permanently over the past two months as an agglomeration of a few incidents. To re-use a word that made us both smile in days gone by, the whole forms a syndrome. Dialectics means, amongst other things, that ends are not indifferent to means; what is going on here drastically demonstrates, right down to the smallest details, such as the bureaucratic clinging to agendas, ‘binding decisions’, countless committees and suchlike, the features of just such a technocratization that they claim they want to oppose, and which we actually oppose. I take much more seriously than you the danger of the student movement flipping over into fascism.”

The term “left fascism,” sometimes now used by both right and left critics to describe Woke ideology, actually originates with another of the core ideologues of the Frankfurt School, Jürgen Habermas, and first appeared in a lecture he gave regarding the student revolts in Germany entitled, “The Phantom Revolution and Its Children.” For both Habermas and Adorno—but less so for Marcuse—student radicals had given themselves over to “voluntarism,” a belief that the conditions of revolution were already at hand, no more theory was needed, and all that remained was the need for action.

Both Habermas and Adorno had lived in Germany during the rise of German fascism; Habermas himself had been a member of the Hitler Youth (he was 9 years old when Hitler was named Chancellor), while Adorno—who was Jewish—left Germany in 1934 after his right to teach was revoked for being non-Aryan. Thus, both had direct experience of really-existing fascism, which none of the students who harassed and threatened them in the late 60’s could have claimed. More so, Adorno was the primary author of a book which in the first decade after its 1950 publication became seen as the authoritative work on fascism: The Authoritarian Personality.

Through no insignificant irony, both men—as well as the entire Frankfurt School—had laid the foundations for the radicalism that swept through students not just in West Germany but also in France and the United States during the 60’s. Particularly influential were their rejections of positivism as relevant to the sociology, meaning that the ways of finding knowledge and testing theories in the natural sciences (biology, physics, etc) were useless for social sciences. This led to a prioritization of personal experience and psychological “structures” (following Althusser) over observable material conditions and theories regarding historical forces.

Along with this belief came an interrogation of how the “authoritarian personality” developed within people. Mixing both Freudian and structural analysis, many in the Frankfurt School iterated a belief that fascist movements tapped into or exacerbated psychological phenomenon that occurred in early child development, especially in families with severe discipline. A child raised in a deeply authoritarian family structure—with a strong and severe father and an obedient and subservient mother—would learn to see the world as a matter of hierarchy and obedience. This would then result in adults who fell in line under strong leaders and unquestioningly followed their commands.

It’s particularly in this analysis that the conspiracy theories about Cultural Marxism begin to correctly identify a social change, while regardless inaccurately describing its causes and intentions. According to the conspiracy, the Frankfurt School sought to undermine the traditional family in order to bring about a Marxist revolution through feminism, the propagation of homosexuality, and a culture of disobedience, sexual deviance, and rebellion, all of which were evident in the youth protests of the late 60’s.

Here the kernel of truth is obvious: the Frankfurt School’s ideas indeed contributed to the theoretical analysis which informed much of the “sexual revolution” and student protests of the 60’s. The Kinderladen movement in Germany, for example, relied heavily on Adorno’s work on Authoritarianism and early childhood development. In that movement, day cares were created in which very young children were urged to explore every aspect of their sexuality (including, horrifically, touching the genitals of parents and teachers). The goal of such encouragement was to prevent the children from internalizing sexual problems which were believed to be precursors of fascist politics.

The abuses of that movement and many others inspired by Frankfurt School theorists are what has given power to the conspiracy theories about Cultural Marxism. However, as evident in Adorno’s letters with Marcuse and Habermas’s public criticisms of the “children” of this phantom revolution, it’s clear what was occurring was not something the “cultural Marxists” of the Frankfurt School predicted or supported.

Rhyd Wildermuth

Rhyd is a druid, theorist, and author living in the Ardennes. He writes primarily at From The Forests of Arduinna, and his most recent book is called Being Pagan.