Being Pagan: Of Gods and Spirits

The most widespread of beliefs among pagan, animist, and indigenous people is that of a world full of spirits and gods. For moderns, however, our ideas about what a spirt or a god is are often hopelessly filtered by fantasy, secular “reason,” and a deep misunderstanding about the past. At best, most of us imagine that the world was once full of such beings but is no more. Or, the Jungian “archetype” model leads us to believe that such things were really just mental constructs which gave earlier people meanings.

So, what exactly is a god? What is a spirit? To answer this question, let’s look at a kind of being typically seen as a pure construction of fantasy: dragons.

A Scourge of Dragons

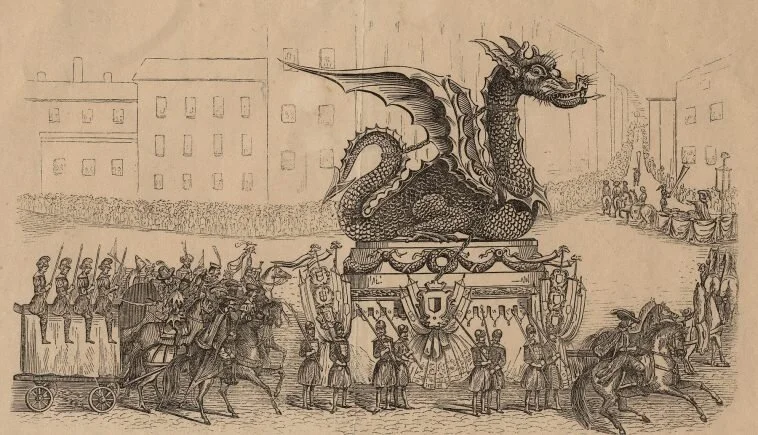

Yearly in the city of the people of the middle mothers, an effigy of a dragon is paraded throughout the city, as it has been almost continuously for at least one thousand years and likely much longer. The name of that dragon is Graoully, and images of it can be found carved into ancient buildings, woven into tapestries, and depicted in statues throughout the 3000 year-old city.

While all this might sound like the beginning of a fantasy novel, it isn’t fantasy at all. The city of the people of the middle mothers (in Latin the Mediomatrici) is only 100 kilometers from where I live, located just between the great forests where the god Vosges and the goddess Arduinna were worshipped. That city is now called Metz, in modern-day France, and Graoully is still marched each year through its streets in the form of a dragon.

Much further south from the city of Metz are other dragons. Two of these are in the lands once held by the people of the giants (the Cavarii), who were part of the larger territory of the exiled peoples (the Allobroges). One of these dragons, Coulobre, no longer has processions or rituals devoted to her. She, a dragon from the cliffs, once was venerated at a gate to the underworld now called the Fountain of Vaucluse, the fifth largest spring in the world.

To the west is another dragon who, unlike Coulobre but like Graoully, is still paraded through the streets of a town. This dragon is La Tarasque, a dragon with a head like a lion and a body like that of a tortoise.

All three of these dragons share a similar history and a similar fate. Each was venerated by the Celtic peoples who inhabited Gaul before and during the time the Roman Empire swept through. Each is associated with sacred rivers and inhabited both the waters and the earth around them. And each, in turn, were also said to have been “conquered” by Christian saints.

The story of the Tarasque is perhaps the most famous of these three. St. Martha, the sister of Mary Magdalene, is said to have encountered the Tarasque in a forest while it ate a man. Sprinkling holy water on it and wrapping the rope of her tunic around its neck, she led it into a village where the inhabitants then pelted it with stones until it died.

Coulubre, at the Fountain of Vaucluse, met a similar fate at the hands of a saint. Veranus, bishop of Vaucluse, is said to have chased her from her home and the place of her veneration into the Alps, where she supposedly died of her own accord.

The story of the fate of Graoully is a bit more elaborate. The tale goes that Clement, a missionary sent to convert the inhabitants of one of the richest and most powerful cities in Gaul, arrived in the city and found it swarming with serpents led by the dragon. He promised the people a miracle: he would rid the city of the beasts if they would first convert to the ‘true faith.’ The people supposedly agreed, and so he made the sign of the cross at the serpents, which made them immediately submit to him. Then, he forced Graoully to return to one of the rivers which flow through the city, to the go to a place where no humans nor beasts lived.

All three Christian tales, as with countless others involving dragons and other beings, were part of a Catholic tradition to explain and prove the death of older beliefs, spirits, and gods. In each story, the new religious order displaced or conquered the older order by magical or miraculous means, and the people who performed those acts were then considered saints (holy people) of the new order.

Dragons of the Land, Dragons of the Water

Such stories are particularly widespread in western European lands, especially in what is now France, Germany, and Spain. They also appear often in the British Isles, such as the idea that Patrick (and also Columba) banished snakes from Ireland (1), and most famously in the story of “St. George and the Dragon,” which is clearly a parallel of the mainland European stories of dragons conquered by saints.

Dragons are such a common theme in these stories that it’s worth looking into them more deeply. While some suggest that the myth of dragon slaying comes from Christianity itself, there are actually no stories or myths about dragons in the Bible except for one from the Apocryphal additions to the Book of Daniel. That section, however, was never referenced by Jewish rabbis in any of their writings, and the earliest known Jewish reference to that section is from the 17th century. Thus, it is most likely a later addition, possibly written by a scribe at the same time that dragon stories were written in Europe.

On the other hand, we do have surviving Celtic stories regarding dragons (and many other stories about gods as well), thanks to the bardic tradition which survived through merger with the Christian monasteries. In the texts they compiled, we find a story about a red and white dragon dwelling in an underground lake who struggle with each other. Those dragons constantly make the land above them tremble, preventing the king Vortigern from building a fortress above it.

We learn in this tale that each of these two dragons is associated with a land: the red dragon is the dragon of the land of what became Wales (2), while the white dragon is of a foreign land. Instead of a saint who pacifies them, it is a boy, Myrddin, born of a human mother and a father from the otherworld. He tells the king of their presence, who then uncovers the underground lake and their prison. The two dragons, once released, fight each other and then eventually return to their own homes, the red dragon back underground and the white dragon to a land across the sea.

From this tale, we see a clear connection between dragons and land (and as in Coulobre and Graoully, with rivers and subterranean water), which provides the key to these other dragon stories in Celtic lands. Likewise, the fact that these stories are so prevalent in Christian hagiography (3) and conversion narratives of the Celtic peoples points to the sacred nature of such beings.

Pagan Celtic stories of dragons appear not very different from the Shinto animist beliefs about dragons, especially in that so many are related to water and rivers. In Shinto, dragons are a kind of kami, a spirit which can be either a god, a force of nature such as wind or rain, a specific place, an object (like a tree or rock), an ancestor, natural principles such as growth, and also guardians.

In Shinto belief, a kami is both invisible yet also obvious and evident, because their presence evokes a human response. European pagan and animist beliefs appear to have been similar: a place itself was inhabited by a spirit, a spirit who was not actually separate from the place but actually also part of the place. The dragon Coulobre, for example, she of the massive and awe-inspiring Fountain of Vaucluse, was both an inhabitant of the place and also the place itself, just as the Tarasque and the place where it lived (now called Tarascon) seem to have been related and inseparable.

Often with these dragon stories there are hints or even clear evidence of religious veneration on those sites. For instance, the massive pool of the Vaucluse has been found to be full of ancient coin offerings, and a druid grove was is said to have been cut down near the spring and a church was built over it.

The Matter of the Giants

Another sacred place points us to a link between land, dragons, and also to gods in the ancient animist belief of the Celts. The famous Mont St. Michel, a monastic complex built upon a tidal island off the coast of Normandy, bears several depictions of the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon. Yet no dragon stories were known to be associated with the mount, but rather two other stories, that of a giant (named Garguntua, from which our English word “gargantuan” is derived) and of a god, Belenos.

Giants in many of the later Welsh and Irish recordings of pagan stories are often associated with gods. For instance the god Brân, whose name means raven, was said to be a giant so large “no house could hold him.” Irish gods such as the Dagda were also said to be giants, and in the Arthurian legends we see the same thing happening to giants as to dragons: Arthur kills them or drives them off in order to establish his Christian kingdom.

While dragons are less common in Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples further to the east, giants very often appear, both as directly related to places or to natural formations (as for example mountain giants) or in the figures of Norse Jötnar. Here, though, we need to speak about the term “giant” itself, which while it now just refers to something large, originally referred to a group of beings in Greek paganism called the Gigantes (thus ‘gigantic’).

The Gigantes were said to be the children of Gaia, born of the earth herself, and were the untamed spirits of natural forces such as wind, volcanic eruptions, storms, and others. They were not necessarily large beings (some were), but because of a translation error by an early Christian, the word “giant” then became used for the Nephilim (the offspring of certain angels and human women, who were said to be massive people), thus causing giant to then always mean “tall” in English.

In fact, the Norse Jötnar were not necessarily thought to always be tall or massive either. Jötnar means “devourer,” and the other word used for them, þursar (pronounced ‘thursar’) means “powerful,” rather than tall or massive.

The giants in the Arthurian legends, the giants in Welsh and Irish pagan stories, the Gigantes of the Greek pagans, and the countless stories of dragons all appear to have one striking thing in common: they are all associated with nature itself, whether that is a specific place of land or water, or with a natural force such as earthquakes, storms, and floods. Here we can see that the ancient animist ideas in Shinto about the kami seems to describe the same group: a class of spirits that come from nature or are expressions of nature itself.

Another parallel that we can draw between these indigenous animist beliefs in Europe and the animism of Shinto is that the dividing lines between what is a god, what is a land spirit, what is an ancestor, and what is a force of nature are not really lines at all. In Norse and Germanic beliefs, the landvættir (land spirits or land wights) are sometimes giants, sometimes elves, sometimes dwarves, and sometimes the spirits of humans or completely impersonal spirits. This has a parallel in many of the Celtic ideas of the faeries, who are not at all the tiny winged beings that modern myth depicts them as. The Korrigan, for example, who are the Breton (a Celtic people in Northwest France) faeries, are actually thought to be the souls of the dead who have become land spirits. The Korrigan are said to fiercely guard old standing stones, alignments, and tombs, killing those who trespass at the wrong time of day.

In both the Welsh lore and also the Germanic lore, giants are sometimes ferociously violent and sometimes kind guardians of knowledge, and sometimes they are gods themselves. For example, the Welsh god Brân was a giant, and was also in the possession of a gift given him by giants who fled from Ireland, a cauldron from the underworld of which they were the guardians. That cauldron was said to return the dead back to life, but those who entered it would not ever speak. Other such cauldrons were held by other giants, and in the Arthurian legends, Arthur slays the giants in order to gain possession of the cauldrons. (4)

In Germanic lore, though the Jötnar are the “enemies” of the gods, many of the gods themselves were descended at least partially from such beings (and Loki was himself a child of two Jötnar). There are two groups of gods in Norse lore, the Æsir and the Vanir, and that second group, which includes the goddess Freyj/Freya and the gods Frey and Njord, appear to occupy a similar category of “earthly” beings as the Greek Gigantes and Irish Fomhoire. They are all “older” gods, all associated with the earth, earthly places, natural forces, and the most basic aspects of life and human interactions with the world around them.

Such gods, spirits, and other beings are usually referred to as “chthonic,” which has taken on the sense of “underworld” or the realms of the dead. However, chthonic in its original Greek (khthon) referred specifically to what lived within the earth, with the sense of the roots of a tree being within (rather than just “under.”) Chthonic beings include ancestors and the dead (because their bodies are put within the earth), but all other spirits that emanate from the buried or hidden aspects of the earth and nature.

This same word, chthonic, came later to also refer to gods of older societies or inhabitants of a place (such as the Fomhoire and the Vanir) who were inherited by later peoples and still recognised. Hecate is one such chthonic goddess and Saturn is one such chthonic god, beings worshiped and revered by people in the lands that later became Greece or Rome. Put another way, they were gods of the land itself, gods who were within the land and therefore needed to be recognised by later pagan peoples regardless of their other gods. In many cases, chthonic gods were also ancestors of other other gods: for instance, the Celtic god Lugh is said in Irish lore to have been mothered or foster-mothered by one of the Fomhoire, the goddess (and likely giantess) Tailtu.

Tailtu is said to have been the mother of farming for the Irish Celts, having tilled all the land herself so that her foster-son and his people could survive. In this story we see another interesting aspect of many of the chthonic gods, as they are often associated with the earliest forms of farming, of settlements, and of providing for people. Freyj, the Vanir goddess of the Norse and also the Germanic peoples (who called her Frey), is a chthonic goddess of fertility and abundance, as well as domestic life, the hearth, and magic.

A God? A Landspirit? Or Both?

This apparent mixing of groups of gods reflects something we can easily forget about the ancient world: people traveled and intermixed. The lines between gods and other spirits is often blurry, and also the lineage of the gods is often very mixed, but this is also true of the people who knew these gods.

As mention, the Vanir gods (such as Freyj) were a different sort of god from the Æsir (such as Odin). But of course, Odin and Freyj married, and Odin himself had giant lineage, as did others of the Æsir. Yet the Æsir and Vanir were said to have been once at war, just as the Jötnar are still at war with the Æsir up to the foretold end of Ragnorok.

While even many who take these stories seriously and recognise the existence of these gods tend to dismiss these lineages as mere details in the lore, the parallels of this sort of intermixing in other pagan lore (Celtic and Greek especially) points to actual changes in people groups. The Vanir, being gods closer to the “chthonic” types of gods and spirits, were likely local gods or spirits of places and of the land itself. That is, they represented a more organic and direct kind of relationship to gods and spirits through the land, while the Æsir appear to be more gods or spirits of communities or people groups.

Freyj is a fascinating example of this, and one personally interesting to me as she is one of the gods I recognise in my twice daily rituals. Not far from where I live is a natural rock formation upon which is carved two figures. The site appears to have been a place of ritual and worship, and it is not far from the ruins of an ancient Celtic town (an oppidum).

The place is now called Freyley, meaning “Freya’s Rocks.” However, the Celtic oppidum and the ritual use of the site pre-dates the coming of Germanic peoples here, meaning that it is highly unlikely the Treverii (the Celtic people who were here before them) worshipped Freyj there. Unfortunately, there is no other evidence or record of who the Treverii revered there, but another site much farther north, as well as the legend of a Christian saint, provides an answer.

In what is now Belgium, there was until the 6th century a stone statue of a huntress woman whom the people worshipped. St. Walfroy, a Christian bishop intent upon converting the local peoples, railed against the worship of the woman and, in one story, supposedly sat on a tall pole nearby, threatening never to come down unless the statue was also torn down. A later writer, Gregory of Tours, states that this statue was of “Diana,” but all the evidence instead points to it being of the goddess Arduinna.

Arduinna is both the name of a goddess and also the name of the forests where she was worshipped, something seen quite often in Gaul and other Celtic lands. That forest, which is called now the Ardennes, once covered all of what is now Belgium, Luxembourg, must of north-eastern France, and the parts of Germany called the Rhineland-Palitanate. Thus, the worship of a huntress goddess in one part of the forest was likely also linked to the worship of a huntress goddess in other parts of the forest. So, besides being attested to in Latin religious inscriptions in the area, there are even later examples of a cult to Arduinna, up to the 11th century, which the Christian church complained about.

So, it is a great likelihood that this spot near my home was used to venerate Arduinna before becoming a site of worship of Freyja (and later named Freyley). Here, though Arduinna was a Celtic goddess and Frejya a goddess of the Germanic peoples, the transition from the worship of one to the other in such sites can’t really be said to be much of a transition at all. Arduinna was both a forest goddess and a goddess of hunting; while Frejya is not directly associated with either, she has a boar companion whom she was said to also ride, linking her to statues thought to be likely of Arduinna also riding or accompanied by a boar.

Are Arduinna and Freyja therefore the same being? No, but this is the wrong and overly modern question. Consider a different question instead: where does a forest end, and where does it begin?

The Ardennes forest once covered all of this area, yet now most of the forest has been cut down or is otherwise divided by roads. The forest where the Freyley stands is no longer connected to the other parts of the forest, yet it once was. Is it still correct to call that forest the Ardennes? During much of the Roman Empire and long before, the Ardennes forest was once part of a much larger forest, the Hercynian forest, which covered much of Europe, extending from the westernmost parts of France to eastern parts of Poland. Is it really true, then, to say that the Ardennes was a separate forest from the Black Forest, the Morvenne, the Vosges, and any of the other forests it was once part of?

In the same way that it is not possible to really define the borders of a forest, it is not possible to define the boundaries people and cultures. When the Germanic Frankish people moved into the lands of the Treveri who previously lived here, the Treveri didn’t disappear, nor did their culture. The Franks and the Treveri married each other, lived amongst each other, and the result was a culture that did not look fully Germanic nor fully Celtic.

The same can be said of all the migrations of peoples throughout Europe, but also the same is true of those in Africa, in Asia, and also in the Americas pre-colonization. When one group arrives, the other group doesn’t just go away. Even if that new group is more dominant, the resulting culture is a reflection of both.

For a fascinating example of this, consider the complicated history of the language I am writing this in, English. English is a mix of Germanic and Romance languages. The Angles and the Saxons were both Germanic peoples who settled in Britain and intermixed with the Celtic peoples who were already there, and the language they spoke up until the year 1066 was a melange of those three currents. In 1066, the French-speaking Normans (who were themselves a mix of Celtic and Norse peoples) invaded Britain, and the addition of their language and culture to what was already there created the English language. Also, ironically, French means Frankish (the Germanic peoples previously mentioned), but the French don’t speak Frankish but rather a language derived from Latin, which was one of the indigenous language from Italy that later became the official language of the Roman Empire. (5)

So, just a forest cannot easily be defined, people groups cannot be easily defined or divided into discrete categories. The same is true of the gods those people revered and knew, as well as their rituals and customs involving those gods. Likewise, just as it is not true to say English is also German, it is not true to say that Freyja is also Arduinna. Nor is it possible to truly say English is a language completely separate from German or from French, and thus we also cannot truly say Freyja and Arduinna are completely separate, either.

Another thing to note in the case of many gods such as Arduinna is that there is no clear division between the god as a separate being and the place they are worshiped or associated with. Goddesses of rivers are often both a goddess of those rivers and also the river itself, such as spirits of trees or springs are both spirits independent of the spring but also indivisible from the spring. In the words of G.K. Chesterton, “the old Greeks could not see the trees for the dryads,” meaning that for pagans, there was little difference between the spirit of the thing and the thing itself.

What to do about the gods

So, now we can return to our original questions: what exactly is a god? What exactly is a spirit? But by now, you’ve probably also understood that this question cannot be answered in the way it was asked, because it was the wrong question.

Still, we can try to answer it by looking at what ancient peoples wrote about them, especially the Greeks. However, in such writing we find that they don’t really know either; rather, they seem as perplexed about the matter as any of us might be now. What they are not perplexed about, however, is that there are gods at all.

Put another way, ancient peoples took gods and spirits as a given the way we now take wind, rain, and storms as a given. We know such things exist, but unless we are a sailor, a farmer, or a meterologist, we rarely actually think about them except when the wind, the rain, or a storm is particularly strong and affecting us directly.

Pagan peoples appear to have looked at the gods and spirits in the same way. Priests, druids, shamans, oracles, mystics, and poets gave their time in contemplation of such things, but the majority of others only ever thought about the gods or spirits unless there was a problem, or they had particularly profound or disturbing dreams, desired a blessing for something they were about to do, or needed help with something they could not resolve on their own. At most, the “average” person tended a small shrine in the home, or visited shrines to ancestors on special days, or made prayers or offerings to a god a few times a year, and participated in community rituals that were often also festivals where the religious significance of the event blended seemlessly with the cultural “entertainment” aspects like drinking, feasting, and meeting potential sexual mates.

That is, the existence of gods and spirits was part of the cultural fabric of life itself, rather than a question to be complicated or a philosophical matter to be unraveled. This has parallels to the way the Catholic churches in small European villages historically (and sometimes still) functioned not just as a religious building, but also as the center of village life, as a place of meeting, of celebration, and a place for many of the other activities that compose community.

This is the way also that the kami are seen in Shinto, the way the gods are seen in Hinduism, and the way gods and spirits were treated in African animist religions as well. Some people become priests and tend the shrines of gods and spirits, but the vast majority of people do not become priests and only occasionally visit such shrines.

Such priests have a kind of role in their societies that is a bit difficult for us moderns to fully understand, and one that is deeply different from the role of a Catholic priest. While both kinds of priests act as intepreters between people and the gods and spirits, the role of the priest in pagan, animist societies is also to make sure the gods and spirits are pleased, lest they wreak havoc.

This role can be best seen in many African animist societies, in which long rituals are performed by priests and the kings or chiefs together to make sure that the gods “stay in their place.” Sometimes, these rituals actually involve chasing gods or spirits out of a community, a home, or even a person, or bribing these beings with offerings or promises so that they will not disrupt everyday life.

While it might be tempting to think of this as parallel to the Christian idea of a “vengeful god,” it’s actually closer to a Catholic exorcism rite. However, in those rites a demon who is wreaking havoc on a human is bound and chased out; in pagan cultures, the spirits are not seen as “evil” or “fallen” but rather just in the wrong place for a reason that needs to be understood and resolved.

Here we can look at two practices that are widepread throughout many pagan cultures: rituals of ancestral remembrance and rituals to hearth or home spirits. Lighting candles or tending a shrine to ancestors is both an act of reverence to them but also an act of making sure they are pleased. That is, it is an act of honor in the sense of its older English meaning: giving respect to and also welcoming as a guest. Or put another way, it is an act of hospitality, a concept deeply important in countless pagan societies throughout the ancient world.

Giving hospitality to a guest in ancient societies involved much more than giving them food or drink. Rather, it was an act of mutual obligation on both the part of the guest and the host, both of which agreed to exchange something with each other through the relationship of hospitality. That exchange was rarely financial or material, but rather a sense of continued obligation on the part of the guest, who would always then seek the best for their host, “returning the favor.”

The word favor comes from latin favorem, meaning kindness, inclination, partiality, or support. To favor someone was to support them or think of them with good will, to be on their side. So in hospitality, in exchange for being favored by the host, a guest thus agrees to later favor the host. Such favor could of course mean merely also hosting at another time, but could also just as often mean physically protecting the host against enemies or arguing in their defense against those who wish that person ill.

So, in ancestral veneration, a person is showing a favor to the ancestors, or returning favor that that ancestors showed to them. It is a reciprocal relationship between the person and the ancestors, one that continues to benefit both the living and the dead.

The second widespread practice, that of creating shrines for hearth or home spirits, is also an act of hospitality. By setting aside a place for such a spirit in a home, they are welcomed into the home in the way a guest would be welcomed, with the literal sense of the words “make yourself at home.”

Stories of helpful house spirits are particularly abundant in Celtic and German lore, many of which have survived through fairy tales that we still learn today. For instance, the story of the shoemaker and the elves, in which an old shoemaker wakes each morning to find his work completed mysteriously in the night, is a such a tale. Those elves have a name, the heinzelmännchen, and they were said even to have helped build cathedrals for overworked masons.

One of the most common aspects of such stories, incidentally, is that such beings appreciate only a tiny bit of attention but no more. In fact, too much attention makes them go away, just as giving them no attention will make them leave. Thus, shrines to house spirits were often very simple affairs, and offerings to them were quite simple (a small bowl of milk, for example, or the bit ends of cakes or breads). There seems to be an importance in acknowledging them in subtle and very sideways manners, more like they are neighbors rather than family members.

In fact, “neighbor” is probably the best way for a modern to understand the pagan relationship between humans and gods and spirits. A neighbor is literally someone who lives nearby, someone whose life and existence is related to yours but not a direct part of yours. The gods and spirits have their own lives and own worlds, just as we do. But we live next door to each other, and just as the lives of our neighbors affect us usually in very subtle ways but sometimes in profound ways, it is the same for the gods, the spirits, and the humans who are each others neighbors.

This work is part of Rhyd Wildermuth’s upcoming book, Being Pagan, which is available for pre-order here.

It is also the text for the course of the same name. The next iteration of this course starts October 2nd.

Rhyd Wildermuth

Rhyd is a druid, theorist, and writer, as well as the director of publishing for Gods&Radicals Press. He lives in the Ardennes. Subscribe to his druidic dispatches at From The Forests of Arduinna.

Many geologists and natural historians point out that there were likely never any snakes in Ireland. We can see the resonance of this story in Clement of Metz, who lived likely 400 years before Patrick. Some have suggested that “snake” was a metaphor for the druids, and though this isn’t certain, regardless the tale is of the same genre as the other stories of the old order being displaced by a saint.

This is the reason for the red dragon on the flag of Wales

The stories of saints

The Celtic ideas regarding cauldrons is deeply fascinating. Ceridwen is said to have brewed a potion of divine inspiration in a cauldron (the Cauldron of Awen). The Dagda (a giant god of the Irish) possessed a cauldron which was always full of food. But also natural places are referred to as cauldrons, which leads to the possibility that cauldrons are themselves a kind of power or spirit of the land.

And to add something even more interesting to this, the Italic Tribes (the peoples of Italy before the founding of Rome) have shared ancestors with the Celts and the Germanic peoples, and Latin shares some similar language forms to Celtic ones. Additionally, Celtic peoples lived in on the Italian peninsula alongside the Etruscans and Latins, so Latin absolutely had Celtic influences.